The Public Radio is an FM radio that tunes to one station and one station only. It’s a passion project co-created by Spencer Wright, of “The Prepared” fame (if you’re not subscribing to this newsletter, get on it!).

This might seem like a great minimalist idea, getting away from hundreds of radio stations and iPhone screens, but the price tag is a surprising $60. A quick look on Amazon and you can find full spectrum AM/FM radios for $20. When you really get into it, the story of the $60 price is similar to the story many electronics manufacturers will tell after working to bring a product to market, and reveals a lot about the process.

Electronics that are “made” in the U.S. often have smaller components made in China.

Like all consumer electronics, many of the components (microprocessors, passives, electro-mechanical components) in The Public Radio are either only made in China or simply not practical to purchase from the US. For instance, the FM receiver module we use is marketed by a US company (Silicon Labs) but made in China, and even the worlds largest electronics brands would have little power to change that. Similarly our speaker could theoretically be made in the US, but to do so would effectively kill our cost structure, probably moving the radio’s retail price well above $100 from an already expensive $60.

This highlights a struggle many manufacturers face. Is buying a U.S. speaker worth an extra $40 on retail price? Even if this was the “right” call, would there be any market viability — anybody to purchase the $100 radio? If your goal is to support U.S. made products, the perfect here would likely be the enemy of the good.

I can’t stress how unusual this is; it’s simply not how things are done. Most consumer electronics rely intensely on the supply chains of the Pearl River Delta – the same places where our speaker, battery clips, knob, and potentiometer (and likely a number of other tertiary components) are made. They’re made in batches between 10,000 and a million, and are then containerized and shipped to large fulfillment centers in places like Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley and Chino, CA. There they sit, sealed in their retail packaging until someone places an order. And when that happens, a relatively low-skilled worker picks it off a shelf and puts it in a box.

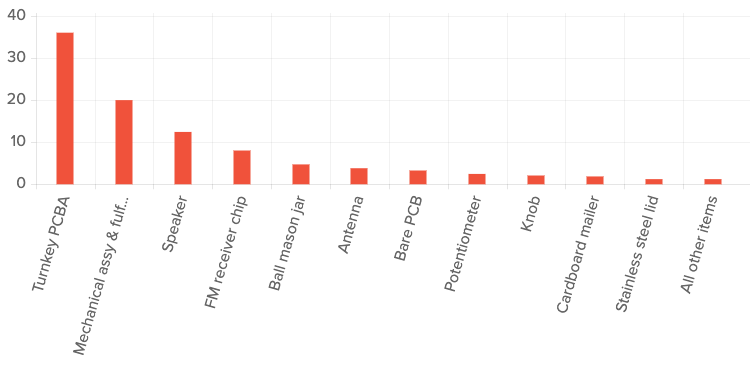

When it comes to product costs, a peculiar factor of the radio is that they are tuned to just one frequency. This makes the units impossible to completely mass produce, requiring a specific tuning step when they are programmed. But it doesn’t add as much cost as you might think. 20% of the COGS is “Mechanical assembly and fulfillment”. You can get that down with scale, but if you’re combining majority U.S. components and U.S. fulfillment, you’re going to have factor in U.S. wages at some point. The 2 minute manual programming stage is likely a pain, but not driving the cost as much as you might think.

The broader story is that at our scale (5-10,000 units per year), consumer electronics is expensive. Purchases at that level simply don’t bring much leverage, and our just-in-time production model ends up being expensive on a per-minute basis (partly due to switching costs).

Incredibly, the $60 is actually a major price hike from what it used to be sold for — a 33% increase from the $45 when it launched.

On the one hand this sounds crazy – we had a relatively successful product that we wanted to sell more of; the typical answer to that scenario is probably not to charge more for it. But the price increase allowed us to offer keystone pricing to brick-and-mortar retailers, and it gave drop-ship retailers significantly more margin to play with – making us a better partner for them as well.

In the meantime, we doubled down on direct-to-consumer sales. This also is a new skill, but I’m happy to say that since our price increase, we’ve managed to more than double both our direct-to-consumer revenue and our direct-to-consumer sales volume; in other words, we’re selling more units and making more money off of each sale.

The Public Radio has found a formula that works. In some ways it’s making its own way, but it’s also a story that’s familiar. If you read the full account (and you should), there is a lot of wisdom to be found.